GME DVD Distribution: End of Semester Update

/Gartenberg Media wishes the best for our university colleagues in these trying times. Due to the sudden advent of remote teaching beginning in March, we decided to suspend our announcement of our spring semester DVD releases until the fall of 2020. Nevertheless we are fully prepared to fulfill prospective orders to the academic community from our entire catalog of more than 200 titles. For a complete list of our DVD/Blu-ray titles and pricing, please click here. There are live links from each title to its individual web page description. We thought this listing would be helpful for university librarians who need to expend their budgets before the end of this academic year in May, as well as for professors anticipating teaching material for their fall curricula.

For your information, we are also in the process of identifying a selection of titles that will be available for Digital Site Licenses in the near future. Please feel free, however, to contact us at any time if you wish to inquire about the availability of GME DSL titles.

In the meantime, we also wanted to share with you some press reviews of DVD titles that we offered for distribution during the winter semester (January – March).

◊

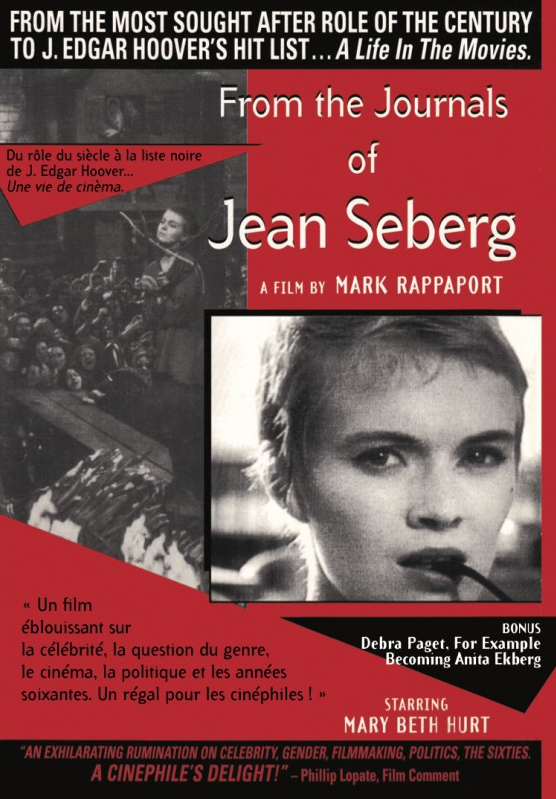

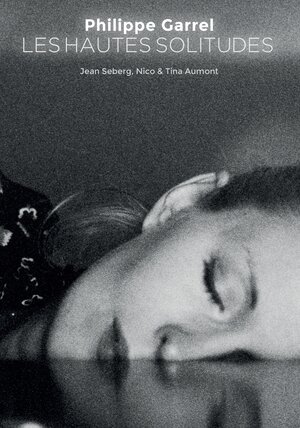

In The New York Times, critic J. Hoberman wrote about Mark Rappaport’s FROM THE JOURNALS OF JEAN SEBERG (1995) and LES HAUTES SOLITUDES (1974), by Philippe Garrel.

“Rappaport might be considered the original ‘VCRchaeologist,’ using clips from old movies as a form of critical analysis. Following his 1992 experimental documentary, ROCK HUDSON'S HOME MOVIES, FROM THE JOURNALS offers a mock subjective account of Seberg’s film career, blending onscreen performance with imagined autobiography and a soupçon of film theory. Mary Beth Hurt – a native of Marshalltown for whom the teenage Seberg actually babysat – stands in as the actress, annotating her movies from beyond the grave. “Who on earth would follow this drum majorette into battle?’ she asks after watching a 17-year-old Seberg, brandishing a sword… ‘JOURNALS is also an exercise in creative editing. The movie concludes with an Oscar-worthy homage, cutting from Seberg’s scene interviewing Jean-Pierre Melville in BREATHLESS on the subject of immortality to a collage of close-ups consumed by flames and underscored by Juliette Greco’s moody rendition of the theme from Preminger’s BONJOUR TRISTESSE of 1958, Seberg’s follow-up to SAINT JOAN…she died at age 40, in an apparent suicide.”

In addition, GME also distributes LES HAUTES SOLITUDES, another experimental narrative featuring Jean Seberg. Hoberman writes that “This 80-minute 1974 feature by Philippe Garrel is composed almost entirely of faces shot in close-up – mainly those of Seberg and the actress Tina Aumont, with the chanteuse Nico making a brief appearance.” In silence and black and white, the focus is on a sole visage, that of a fallen 40-year-old star, Jean Seberg fifteen years after BREATHLESS, struggling with alcohol, fear , loneliness, chemical dependence and dementia. in an hour and fifteen minutes consisting almost exclusively of close-ups, an entire lifetime rises to the surface of a face.

◊

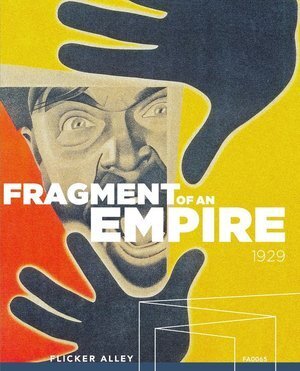

In the scholarly journal Quarterly Review of Film Studies, Editor-in-Chief David Sterritt commented on DVD editions of two silent classic films made at the apotheosis of the silent era, L’ARGENT (Marcel L’Herbier, 1928), and FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE (1929, Fridrikh Ermler).

Sterritt wrote that “FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE centers on a young man named Filimonov who fights in World War I as a Russian soldier, is severely traumatized in combat, eventually comes to his senses, and reenters society…dazed and confused by a once-familiar land given drastic new form by the Bolshevik Revolution during his slumber…FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE is celebrated mainly for its bravura montage sequences – several episodes are edited with a speed and precision that stands out even in the spectacular context of 1920’s Soviet cinema – but other elements are no less impressive, from the finely tuned acting to the audacious cinematography, sometimes realistically detailed, sometimes stylized to the point of abstraction.”

FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE was released on October 28, 1929. One of the problems in terms of contemporary re-evaluation of this film has been that numerous public screenings of this film in 1929-1930 gave evidence that both its language and the multilayered narrative were too complicated for the “masses”. It was decided to make a simplified, abridged version of the film – mainly for distribution in villages. It seems that what was known as the “canonical” version of Ermler’s masterpiece, is in fact this village adaptation. What was lost in these abridged version was the image of Christ in a gas mask (a reference to George Grosz’s anti-military drawing) as well as the story line surroundin Filmonov's cross including symbolic references to the subconscious. Additionally, although the film was widely distributed at the time of its original release, each country had a censorship of its own. The German version was re-edited by Belá Balás, the film theorist, critic, and writer; the French version was severely re-edited and incorporated a jazz soundtrack. Fortunately, a montage list for the film from Gosfimofond, the Russian state film archive, was used to restore the film close to its original version. This digital edition of this film was compiled from nine different versions found in archives throughout the world, and now reveals that FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE deserves a place as one of the canonical films of the silent era. The bonus material on this digital edition (published by Flicker Alley) includes a booklet on the film’s history, style, and restoration; a commentary track featuring Russian film historian and curator Peter Bagrov on the significance of this film; and a documentary by historian Robert Byrne on the film’s restoration.

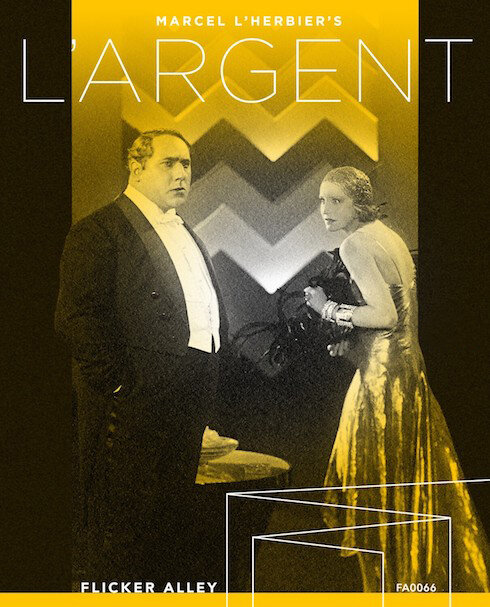

Marcel L’Herbier’s financial melodrama L’ARGENT was based on the 1891 novel by Émile Zola. The story concerns a wheeling-and-dealing capitalist who teams with an idealistic aeronautical engineer as part of a scheme to defeat a rival financier, then gets into a romantic conflict with the engineer’s wife and plots a fraud-based revenge against her when she resists his advances. Known for his ability to translate artistic and innovative sensibilities into commercial fare, L’Herbier designed L’ARGENT to compete with the super-productions coming out of France, the United States (THE KING OF KINGS), and Germany (METROPOLIS). It is thus bursting with state-of-the-art techniques, a big-name international cast (including Brigitte Helm of METROPOLIS fame), 1500 extras, and was shot by France’s highest paid cameraman at the time, Jules Krüger. L’Herbier made use of a dozen cameramen flying on pulleys and dollies, as well as an unmanned camera that descended and revolved to capture the stock exchange in full frenzy. Even as the pilot embarks on his trans-Atlantic flight, action on the stock market floor intensifies in a montage of Eisensteinian proportions. To quote Mireille Beaulieu, who wrote the essays for the booklet that accompanies this digital publication, in L’ARGENT “movement is central and rhythmic, evolving through the progression of a given scene within the complex relationships between the camera, the actor, and the set. Discovering or rediscovering L’ARGENT is above all a sensory experience, an immersion in a work of vibrant beauty.”

This digital edition also includes an additional accompanying bonus feature, AUTOUR DE L’ARGENT, made by Jean Dréville, a 22 year old film journalist, photographer, and graphic designer, who was engaged by L’Herbier to document the production of L’ARGENT . Dréville’s admiration for Marcel L’Herbier’s work is evident. Hiding behind support beams in the rafters of the studio hangers, he was able to capture L’Herbier’s complex cinematic techniques (lighting, cameras, and tracking shots, as well as the construction of the gargantuan sets). He transforms the footbridges of the studio into avant-garde, stylized geometric lines and creates a short montage to the glory of technology. And, as Sterritt observes in his review:

“Zola described the Paris stock exchange as a virtual combat zone where ‘mysterious financial operations which few French brains can penetrate’ transpire amid a cacophony of ‘gesticulation and savage cries.’ Transferring this to the screen, L’Herbier flew cameras through the air and made bold use of the wide-angle Brachyscope lens, which descends from the exchange’s lofty ceiling to convey with vertiginous exactness the effect of ants teeming in an overcrowded nest.”