In Celebration of Black History Month, GME Highlights Photographer Hugh Bell and The Kamoinge Workshop

/“HOT JAZZ” (1952) BY HUGH BELL.

In 1955, Edward Steichen, then Director of the Photography Department at MoMA, mounted an exhibition of images from around the world as a “manifesto for peace and the fundamental equality of mankind.” That exhibition, titled The Family of Man, quickly became a 20th century cultural phenomenon and was added to UNESCO’s Memory of the World register in recognition of its historical value. “Hot Jazz” (pictured here) by Black photographer Hugh Bell (1927—2012) was selected for this ambitious exhibit.

In his book A LIFE IN PHOTOGRAPHY, Steichen noted of The Family of Man: “The people in the audience looked at the pictures and the people in the pictures looked back at them. They recognized each other.” This project was a fitting platform for Bell’s work. Dubbed a “poet behind the lens” in Thomas Allen Harris’ 2014 documentary THROUGH A LENS DARKLY: BLACK PHOTOGRAPHERS AND THE EMERGENCE OF A PEOPLE (based on Deborah Willis’ seminal book REFLECTIONS IN BLACK: A HISTORY OF BLACK PHOTOGRAPHERS 1840—PRESENT), Bell’s images are notable for their candid and intimate qualities. He had a unique ability to cull visual poetry out of moments big and small. Bell himself noted: “Each picture should have a little message, or a little feeling about something… some little ‘something’ in the photograph that comes alive, tells a story.”

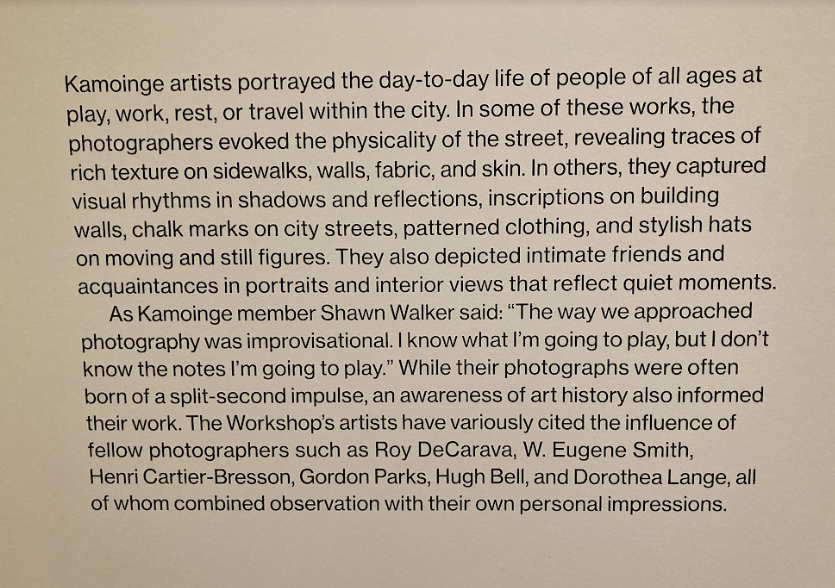

The humanistic ethos found in Bell’s work became a major tenet of The Kamoinge Workshop. The Workshop was an artist collective established in 1963 when two New York-based groups of African-American photographers came together “in the spirit of friendship and sought artistic equality and empowerment.” The commitment of the collective was to support Black photographers and “emphasize photography’s power as an independent art form that depicts Black communities as they saw and experienced them, in contrast to how they were often negatively portrayed in art, media, and popular culture.” Kamoinge’s collaborative and improvisational aesthetic, which is “rooted in the complementary art forms of photography and music, specifically jazz,” finds kinship with Bell’s suite of images of Jazz Greats from the 1950s.

While Bell has long been overlooked in academic and cultural discourse, his impressive body of work and impact on Black photographers has begun to earn belated recognition and reappraisal. Though not a member of the Kamoinge Workshop, Bell was cited as a major influence — alongside Gordon Parks, Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, Henri Cartier-Bresson, and Roy de Carava (who was a founding member of the Workshop and whose work was featured alongside Bell’s in The Family of Man) — in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s Kamoinge retrospective in 2020. This exhibition was originally presented at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts and organized by Sarah Eckhardt, Associate Curator of Contemporary and Modern Art at that institution.

GME is proud to exclusively manage the photo archive of Hugh Bell. Our mission is to further the artist’s legacy via placement of the collection in a cultural institution, the organization of museum exhibitions, and the licensing of his photographs for documentary films and book publications. For requests related to these initiatives, please contact GME’s Fine Arts Curator David Deitch at david@gartenbergmedia.com.

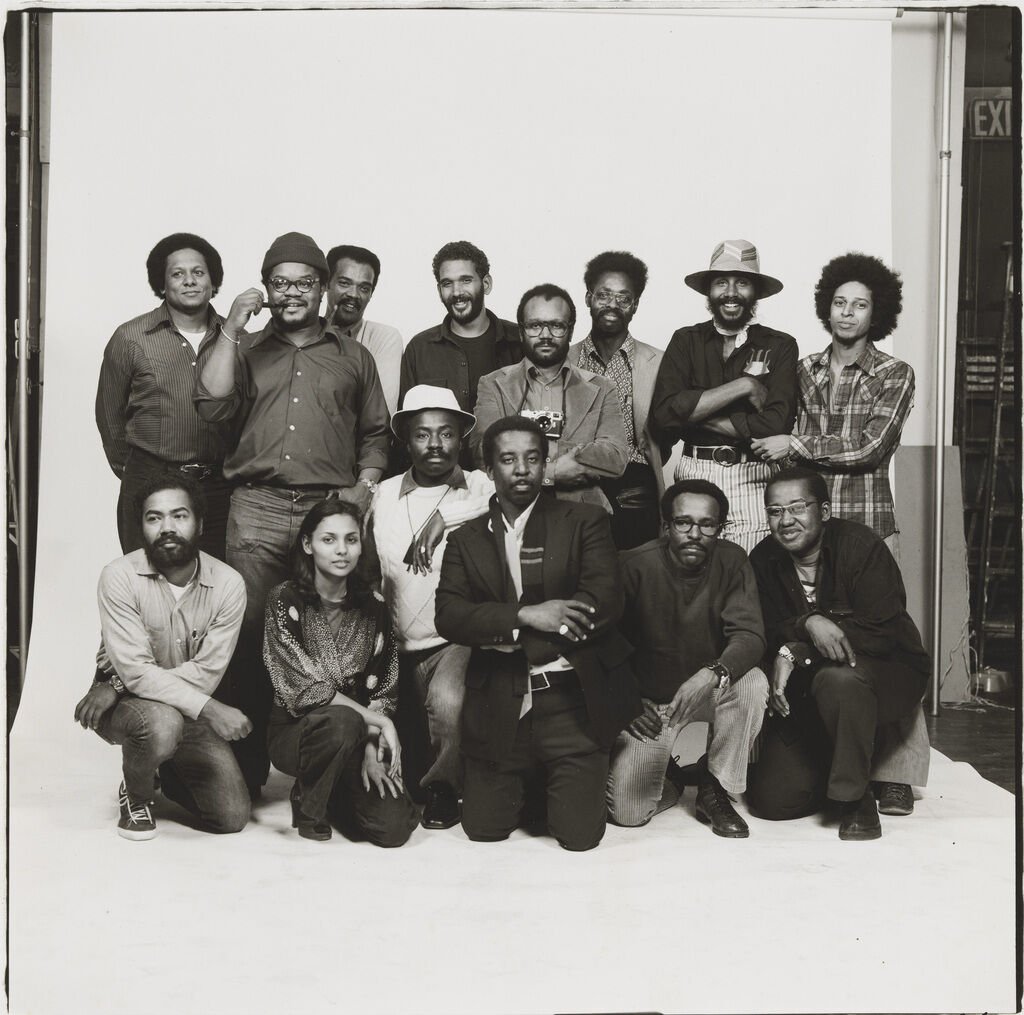

All photographs © The Estate of Hugh Bell, except for the Kamoinge Workshop group photo taken in 1973 (Anthony Barboza) and the Whitney exhibit wall text (Jon Gartenberg and David Deitch).