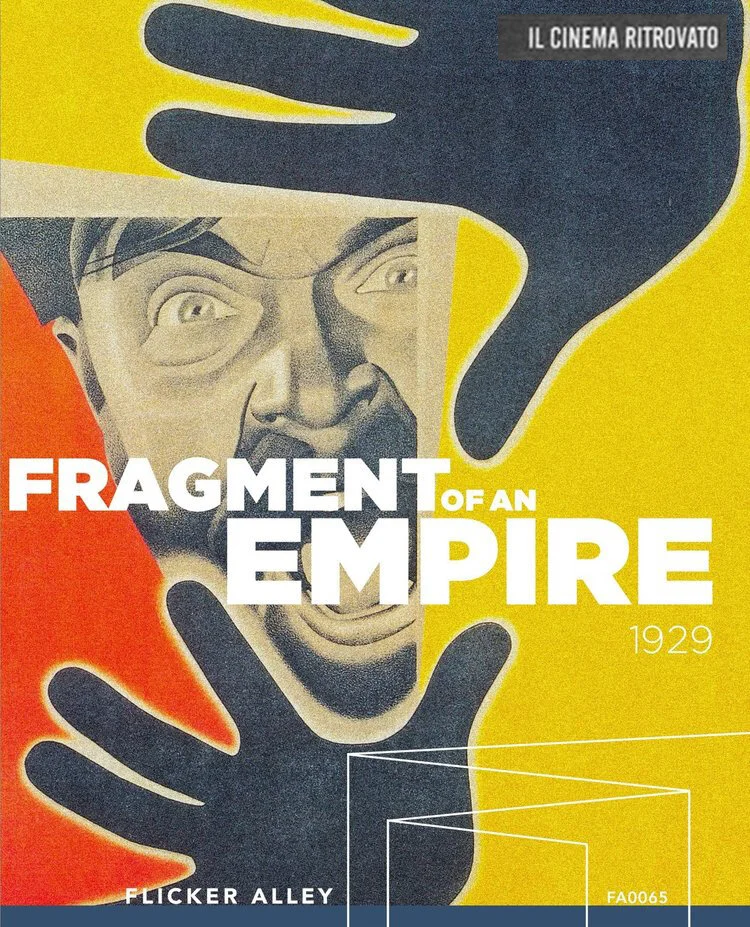

FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE receives The Peter von Bagh Award at the 2020 Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Publishing Awards

/The text presented with this prestigious award from the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival remarks on “an exceptional presentation of a silent film—a revelatory restoration”, and further, “We applaud the newly composed score by Stephen Horne Frank Bockius and the recreation of Vladimir Deshevov’s original piano music from 1929, as performed by Daan van den Hurk.”

2020 The Peter von Bagh Award

The end of the silent era (1928 and 1929) saw an apotheosis of the art and craft of the motion picture, just as the advent of sound was overtaking the motion picture industry. At a time when film theaters were being wired for sound, studios produced “talkies” that were more stage-oriented. The height of artistic achievement in late-era silent films was visually demonstrated in films emanating from France, Germany, the United States, and the Soviet Union; these countries produced masterworks of sweeping camera movement and rapid-fire montage. Fridrikh Ermler (FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE, 1929), is a lesser-known but still significant filmmaker of the Soviet era (see Soviet Film Titles) alongside other directors, including Lev Kuleshov, Sergei Eistenstein, and Dziga Vertov.

◊

Among the exceptional generation of Soviet directors who emerged during the first fifteen years of Bolshevik rule, Fridrikh Ermler is the least well known. “If influence is the criterion for determining the significance of a film director,” writes Russian film scholar Denise J. Youngblood, “then Fridrikh Ermler is perhaps the most important director in Soviet film history.” Why he does not join the ranks of Eisenstein, Kuleshov, and Vertov as one of the great masters of Soviet filmmaking is unknown. Yet his legacy as an intricate craftsman of deceptively simple stories layered with psychological depth and technical proficiency lives on in his work.

Ermler grew up poor in a shtetl; as a movie-mad teenager, he dreamt of being a film actor. In 1923, following his military service, he enrolled in the Institute of Film Art in Petrogad. His filmmaking career extended from 1924 to 1965. FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE, like Ermler’s previous “realist” films – KATKA’S REINETTE APPLES (1926), THE PARISIAN COBBLER (1928) and HOUSE IN THE SNOWDRIFT (1928) — reflects the emerging Communist cultural principles because it highlights the fate of individuals in a way the party regarded as accessible to the millions. Ermler sincerely believed that if everything happening in the country was not necessarily good, it was nonetheless expedient: Things were following the correct path. And since the path was correct, there was no sense in distorting or decorating reality. Ermler was able to complete his film, seemingly without compromise, in the wake of the Communist Party’s first major salvo against decadent Western film styles at the conference on Soviet cinema the political leadership staged in March 1928 to rein in the Soviet directors’ stylistic experiments. But the film itself as a whole is anything but orthodox.

◊

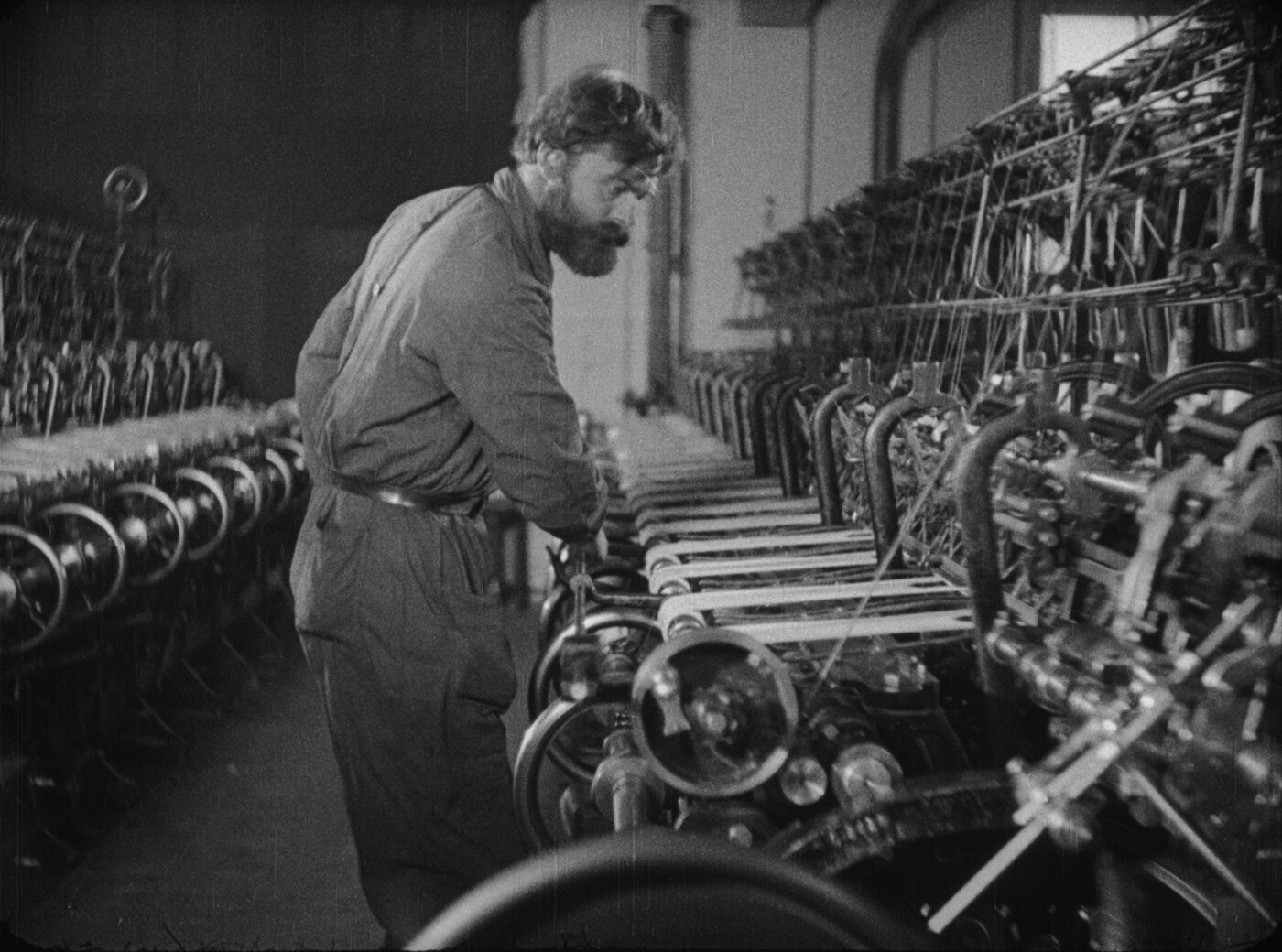

FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE was Ermler’s last silent feature and the last of four productively contentious collaborations with the method actor Fiodor Nikitin. He plays a factory worker, Filmonov, who is traumatized by shell-shock while serving as a soldier in the Czar’s army during the First World War (see Films on World War I and Its Aftermath). He loses his memory and identity for ten years -- precisely the period in which the Bolsheviks won their revolution over the Tsarists and began the construction of the new Soviet Union. Ermler’s intention was to show the renewal of the country, the accomplishments of the Soviet system, and the liberation and rebirth of the people through the eyes of Filmanov.

To prepare for his part as Filimonov—a soldier suffering from total amnesia due to shell-shock from the Great War—Nikitin apparently disguised himself as a doctor’s assistant in the Forel Psychiatric Clinic, where he studied actual amnesia patients. Ermler, meanwhile, may have drew upon his own first-hand knowledge of war as a former spy of the Tsarist Army to create a profoundly realistic and moving portrait of a man whose memories begin to awaken in concert with the radical transformation of the Bolshevik Revolution of October 1917. His projection of the blankness and underlying torment of an amnesiac is palpable and authentic.

◊

◊

FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE was released on October 28, 1929. One of the problems in terms of contemporary re-evaluation of this film has been that numerous public screenings of this film in 1929-1930 gave evidence that both its language and the multilayered narrative were too complicated for the “masses”. It was decided to make a simplified, abridged version of the film – mainly for distribution in villages. It seems that what was known as the “canonical” version of Ermler’s masterpiece, is in fact this village adaptation. What was lost in these abridged version was the image of Christ in a gas mask (a reference to George Grosz’s anti-military drawing) as well as the storyline surrounding Filmonov’s cross including symbolic references to the subconscious. Additionally, although the film was widely distributed at the time of its original release, each country had a censorship of its own. The German version was re-edited by Belá Balás, the film theorist, critic, and writer; the French version was severely re-edited and incorporated a jazz soundtrack. Fortunately, a montage list for the film from Gosfimofond, the Russian state film archive, was used to restore the film close to its original version. This digital edition of FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE was compiled from nine different versions of the film found in archives throughout the world.

Furthermore, this newly-restored film highlights the leitmotif of faces in the first half of the film. Crucially important details become not only visible, but striking, such as the close up of a dog, with a gun pointed at the animal. The dog’s face is intercut with those of the soldier dying of typhus, of another about to be crushed by a tank, and of Filmonov himself. The second half of the film has a Constructivist look with geometric visuals that extol the virtues of modern Soviet society. The world in which Filmanov finds himself is best represented by the canteen sequence. The top level of a double-deck balcony contains a square table with a square board on top of it — revealed as a chess board decorated with sixty-four more squares; the lower deck contains a rectangular ping-pong table which is, in turn, divided into four smaller rectangles.

◊

In the most recent issue of Cineaste magazine, noted film scholar Stuart Liebman articulates the modernity of this impressive film. He writes that FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE is “a unique hybrid film of considerable psychological and artistic sophistication.”

“Contrary to what might have been expected of a Communist who generally toed the party line, Ermler reveals how much of a ‘cosmopolitan’ he was at the time and how fully conversant he had become with the Western ‘decadent’ styles his party’s leaders denounced. He impressively synthesizes several different, cutting-edge contemporary film styles to serve as a kind of bridge between them and the more restricted norms of Soviet cinema. In a scene where the workers eat lunch in a factory while listening to an edifying lecture on the need for women in the workplace, Ermler’s debt to the American editing patterns that all the leading Russian directors learned so much from is evident...Ermler modifed their use, inserting large close-ups of microphones and loudspeakers in rhythmic counterpoint to the workers as they chowed down what looks like a substantial multi-course meal that few Soviet workers ever enjoyed.

Even more impressive is the bold way in which Ermler devised lengthy subtle, hyper-kinetically edited sequences of precisely the sort associated with Vertov or Eistenstein, the pace-setting Soviet advocates of rapid montage, or with Western avant-garde filmmakers like Ferdinand Léger whose BALLET MÉCANIQUE (1924) anticipated the “mechanical symphonies” that became a vogue in Western Europe. Perhaps the most astounding of these occurs at the moment when the factory workers extol all the progress being made in the USSR. A sequence follows of perhaps 150 brilliantly edited shots, some only a few frames long, that are dynamically interwoven by dazzling cuts on internal movements and graphic shapes within the frame…At other key moments, most notably when Filmonov’s memory begins to revive, Ermler fashions sequences that clearly reflect his awareness of contemporary radical experiments in conveying psychological interiority – a kind of cinematic equivalent for a novelist’s free indirect discourse – made half a continent away in Paris by French and White Russian filmmakers.”

Ermler had become swept up in Freudian theory shortly before beginning FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE, and this had direct impact on the most famous scene in the film: the return of Filmonov’s memory. Seeing a glimpse of a woman’s face (his former wife) in a train window, Filmonov freezes and, deeply shaken, slowly walks back to his little house. He lowers himself onto a stool in front of a sewing machine and automatically begins to turn the handle. He turns it faster and faster, while on screen the needle jerks up and down. The sewing machine is transformed into a machine gun. Then, another shot of the woman from the train. And now, here she is in her wedding dress. Filmonov turns the handle with even more passion and suddenly falls off the stool because of the tension. The cross he wears beneath his undershirt slips out; it is the Iron Cross he wore from WWI. Along the floor the spool of thread rolls straight toward the camera, up to an extreme close-up. From the same angle a cannon rolls toward the viewer. Another series of crosses concludes with a large Crucifix somewhere on the battlefield, revealing Christ in a gas mask.

◊

Due to this restored digital edition of the film, FRAGMENT OF AN EMPIRE deserves a place as one of the canonical films of the silent era. The bonus material on this digital edition includes a booklet on the film’s history, style, and restoration; a commentary track featuring Russian film historian and curator Peter Bagrov on the significance of this film; and a documentary by historian Robert Byrne on the film’s restoration.

◊

Related Films of Interest Available from GME: